How To Avoid Planning Fallacy Bias?

Sorry, there were no results found for “”

Sorry, there were no results found for “”

Sorry, there were no results found for “”

Bursting with (over)confidence after successfully building the Suez Canal, Ferdinand de Lesseps attempted to construct a sea-level canal across the Isthmus of Panama. Unfortunately, he grossly underestimated the engineering challenges of the Panamanian terrain.

Beset by diseases and a lack of expertise, he had to abandon the project in 1889. His company went bankrupt after spending $287 million on it.

De Lesseps was the victim of what psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky call the “planning fallacy.”

What is the planning fallacy? Why are we susceptible to it? How do our biases show themselves in our work and life? And what can we do to mitigate the planning fallacy? Read on to find out!

In 1979, psychologists Kahneman and Tversky defined planning fallacy as “the tendency to underestimate the amount of time needed to complete a future task, due in part to the reliance on overly optimistic performance scenarios.”

Simply put, planning fallacy is a cognitive bias that leads you to underestimate task completion times, and overestimate your ability to get it done.

Some of the characteristics of planning fallacy are as follows:

Why does it happen, though?

Humans perceive events asymmetrically. We have an innate desire to be positive and hopeful. We want to believe that we have the power and control to get a task done, even when all the evidence indicates otherwise. Here’s why.

When we set out to plan a project, we are likely to focus on the positive. We believe that we’ve learned our lessons from past failures and are better today. We want to make a plan that makes us look and feel good.

How often have you heard a developer say, “That’s a five-minute bug fix”? The developer believes they are skilled enough to resolve the bug in five minutes, but the reality is far from it.

Change requires us to modify our initial view of the world. In the middle of a project, if we receive new information that shows us we’re off track, we respond by rejecting it.

Project managers often overlook large deviations in progress as minor blips because anchoring bias kicks in. They anchor their thought process to the initial plan rather than the new information.

When we’re in the middle of a project, especially when a good amount of work is done, we don’t like to hear bad news. We disregard Information that challenges our optimistic outlook because it can disrupt the project entirely.

In fact, we see those who take negative information seriously as cynics or naysayers. As a result, peer pressure and conformity bias lead them to embrace the popular sentiment.

Bungee jumpers believe they have a lower risk of injury than other jumpers, despite the fact there is no data to support this. In a more down-to-earth example, we assume managing a full-time job and a side hustle is easy! These are exemplary of optimism bias.

Research shows that optimism bias is one of humans’ most consistent, prevalent biases. It stems from two cognitive tendencies: People overestimate the likelihood of positive events happening to them and underestimate the chance of adverse events.

The tendency and social pressure to maintain an unrealistically positive outlook lead to overconfidence, poor risk assessment, and a lack of contingency plans.

Optimism bias fuels planning fallacy among project managers in a few key ways.

Motivated reasoning is a form of emotional bias where you accept evidence that aligns with your current beliefs and reject any information that contradicts that state of mind.

For instance, if your client wants a website developed in two weeks, but you know that project execution will take longer, you agree to it. You convince yourself that it’s only five pages, you already have a template, the content is ready, etc.

Here is how this fuels planning fallacy:

We’re all a little biased, confident, optimistic, and motivated. So, what’s the harm, you might ask.

When you fall for the planning fallacy, you will likely get several things wrong. This can have extreme consequences.

Misunderstanding timelines: The planning fallacy causes teams to underestimate the time needed to complete innovative projects. You might be too confident to make space for experimentation, failure, and rework. This leads to over-optimistic time predictions that don’t account for a project’s full scope.

Low budgets: When you convince yourself that something can be done quickly, you also underestimate the resources it needs. So, you might hire just one writer to complete an ebook, which actually needs the services of a writer, editor, and designer.

Ignoring external risks: The planning fallacy acts as a blinder, pushing teams to focus narrowly on specific tasks and overlook external risks, such as the regulatory environment, competition, market dynamics, etc.

Self-imposed pressure: Teams feel compelled to provide overly optimistic timelines to get projects approved and funded, even if they know the estimates are unrealistic. This creates pressure, setting employees up for failure and burnout.

Stifled innovation: Innovative projects are complex and uncertain, making it difficult to estimate the time and resources needed accurately. Project planning in such cases is ripe for biases. Underestimating the time it takes to create something entirely new will undermine the very objective you’ve set for yourself.

If you’re scoffing right now under the assumption that only the young or overenthusiastic are susceptible to the planning fallacy, think again.

Planning fallacies don’t discriminate between small software development and large infrastructure projects. Here are examples of how unrealistic plans, biases, pressure, and shareholder expectations have impacted huge endeavors throughout history.

One of the most recognizable structures in the world, the construction of the Sydney Opera House was delayed by at least a decade by planning fallacies. The original estimate, as reported in 1957, was $7 million, with an estimated completion time of six years. A scaled-down version of the original finally opened 16 years later at a cost of $102 million!

The Sydney Opera House struggled because of:

In 1871, the colony of British Columbia agreed to become a part of Canada. In exchange, Canada promised a transcontinental railway connecting the territories.

The project, which was to be completed by 1881 with $25M in credit, took four years longer than planned and required an additional $22.5 million in loans. Here’s why.

On October 20, 2013, President Barack Obama said, “There’s no sugar coating: the website has been too slow, people have been getting stuck during the application process and I think it’s fair to say that nobody’s more frustrated by that than I am.” He was speaking about the highly-anticipated healthcare.gov website.

One of the biggest reasons for this grand failure was the planning fallacy.

The positive from this debacle is that you’re not the only one who planned a 12-month software development project that’s going on 18 months and then some.

Or maybe you can forgive yourself for allocating 15 minutes to tidy up your home, only to realize that you were still cleaning three hours later?

The planning fallacy has consequences in our personal and professional lives. It creates unnecessary pressure, keeps us drowned in our biases, and causes a vicious cycle of overwork or underperformance. To avoid that, you need data, planning frameworks, and an open mind.

Believing that you can get something done in less time than it really takes is among the most common errors of judgment, both in personal and corporate life.

The solution: practice, practice, practice. It takes practice to catch yourself falling into the planning fallacy trap and even more practice to get into the habit of building structures to prevent yourself from succumbing.

Here is a step-by-step guide on how to approach it with the right intentions, processes, and a strategic planning software like ClickUp.

Look at the task completion time the previous time from start to finish. Use the techniques of reference class forecasting—essentially, the process of forecasting the future based on similar tasks, past situations, and results.

By analyzing how comparable projects fared in the past, you can make accurate predictions based on patterns of delays, challenges, and project cost risks.

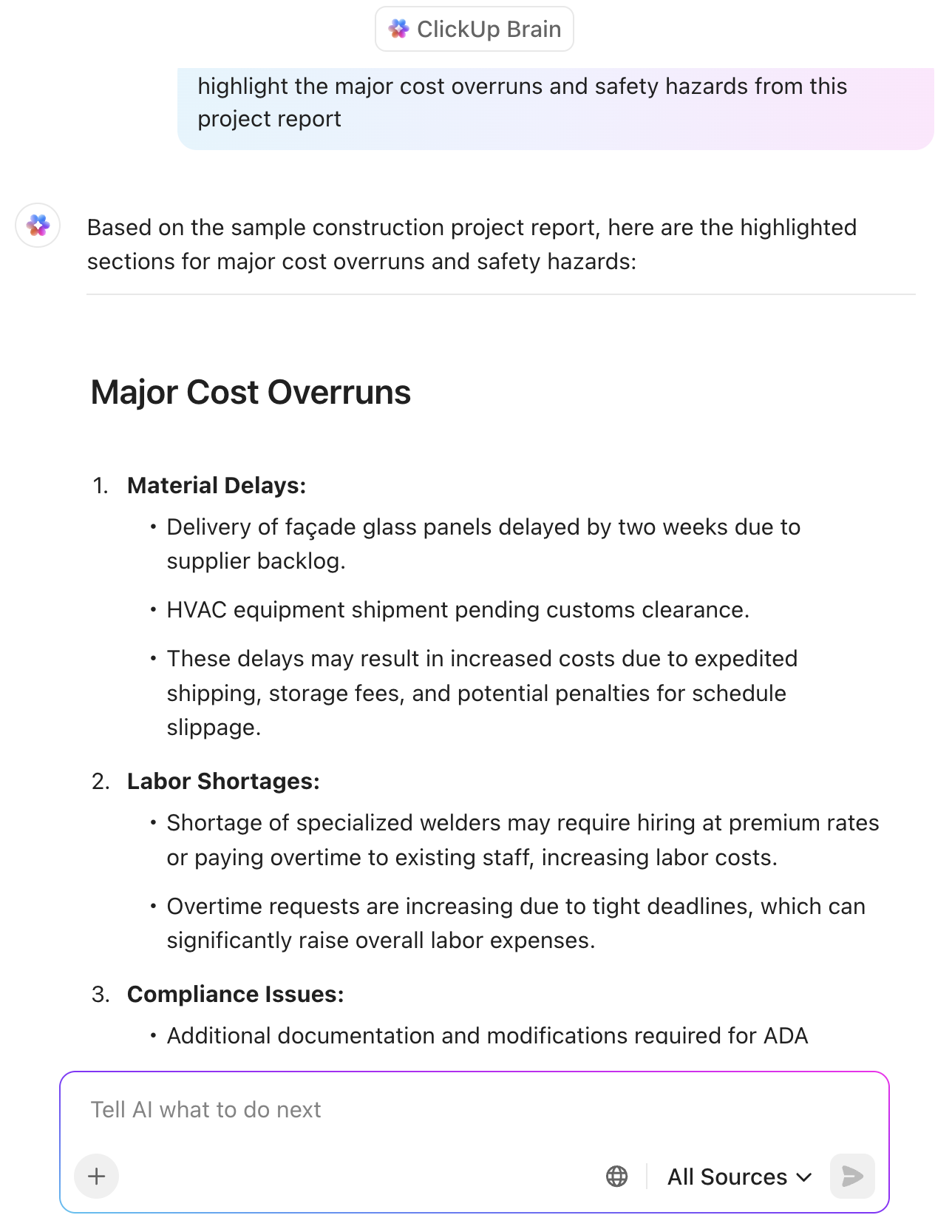

Capturing and maintaining historical data is the trickiest part for most businesses. ClickUp’s project planning tools are designed to gather and curate information on how your work is going.

ClickUp Time Tracking allows you to monitor how long a task takes. The ClickUp Workload view enables teams to record their availability and project managers to allocate resources accordingly. ClickUp Goals lets you set targets and track progress in real time.

If you’re building a product, ClickUp for Product Planning has everything you need to avoid the planning fallacy, including estimates, time tracking, and customizable dashboards. It leaves nothing to chance or your own giddy optimism!

Implementation intentions are ‘if-this-then-that’ strategies used to regulate one’s own behavior or create habits. They are simple, realistic, and actionable ways to work toward project management goals.

Set specific implementation intentions for how and when you will complete the work. Use ‘if-then’ statements, such as:

Using a project management tool like ClickUp provides a simple and visual way to handle dependencies. ClickUp Tasks allows you to connect items and add dependencies so you never miss one. Use the Gantt chart view to visualize the impact of delay and implement corrective procedures accordingly.

When needed, perform a thorough SOAR analysis to identify your strengths, opportunities, aspirations, and results.

Approaching the project this way overcomes optimism bias by deliberately considering adverse situations.

In education, the segmentation effect aims to improve learning outcomes by breaking down lessons into small segments rather than as continuous elements.

In project management, it simply means breaking a large project into smaller parts, which makes it more manageable. While doing so, consider the following.

Use the three-point estimation method to counter the planning fallacy and develop a more realistic project timeline. It involves three different scenarios when estimating task duration.

The weighted average of these three gives the most likely estimate for the task. Try creating your own three-point estimate for the time taken for each task with ClickUp Time Estimates.

Project managers often rely on intuition to estimate how long something will take. This leads to making unnecessary calculations over and over again. Avoid that with customized templates for your needs.

Project pre-plan: ClickUp’s Planning Document Template helps set the project team up for success by capturing objectives, goals, and action items. It also helps break down tasks into manageable chunks for faster delivery.

Project planning: ClickUp’s Planning a Project Template is a beginner-friendly framework for planning future tasks instantly. It empowers you with the structure to develop a plan, organize tasks, prioritize high-impact activities, and align team members all in one place.

Decision-making: ClickUp’s Decision Making Framework Document Template helps you swiftly and accurately weigh the pros and cons of any decision by:

Not finding what you need? Check these ten free strategic planning templates to create a framework to use for whatever decision you need to make.

Popular wisdom goes that pessimists are more likely to survive a zombie apocalypse because they will keep their guard up, plan for worst-case scenarios, make difficult decisions, and abandon preconceptions.

While project management is not always a zombie apocalypse, a bit of pessimism helps.

A pessimistic perspective leads to more realistic assessments, building in buffers and contingencies. It will push you to look at past data and identify everything that can go wrong, giving you a more rational understanding of your strengths and weaknesses.

What’s better than a pessimist? A pessimist with the right tools to visualize project plans and evaluate them.

Daniel Kahneman, in his book ‘Thinking, Fast and Slow’ said: “Most of us view the world as more benign than it really is, our attributes as more favorable than they truly are, and the goals we adopt as more achievable than they are likely to be.”

What Ferdinand de Lesseps couldn’t do, the United States of America United States of America accomplished with the Panama Canal. They went full textbook, diligently using historical data to make realistic estimates, planning for every possible outcome, conducting a thorough survey, and aligning every stakeholder for the project. They completed the project in ten years.

Despite the innumerable examples warning against it, the planning fallacy is a pervasive cognitive bias that misleads people and teams to underestimate the time, costs, and risks of future tasks and projects.

While you can use all your willpower to avoid it, setting up the right systems might help more.

Problem-solving and risk-management software like ClickUp is one of the most effective tools for making data-driven, realistic decisions. With project management features, data focus, intuitive templates, and purpose-designed AI, ClickUp structures your thoughts and clarifies your decision-making. Take ClickUp for a spin. Try ClickUp for free today.

© 2025 ClickUp