The Chunking Method: How to Remember and Recall More

Sorry, there were no results found for “”

Sorry, there were no results found for “”

Sorry, there were no results found for “”

How does a pigeon remember to return to your balcony each time?

How does a rat know which lever to pull to get out of the cage? Or how does a Chess Master memorize over 50,000 patterns of pieces on the board?

Simple answer (rooted in psychology research): Chunking.

70 years ago, American psychologist George A. Miller popularized the concept of chunking as a way to understand and expand short-term memory.

Let’s fast forward to today.

Your sensory systems, sight, sound, taste, touch, etc., are gathering around 1 billion bits of data per second right now. So Chunking might just be what we need to clear the thought clutter.

Chunking is the process of grouping individual bits of information into a sequence or a pattern that makes it easier to capture in our working memory and store in the long-term memory for later recall.

Even if you haven’t heard of chunking before, you’ve certainly done it.

Think of the way your Social Security number is represented: XXX-XX-XXXX, with chunks of three, two, and four digits. To remember the names of my seven cats, I chunk them into litter mates: three duos and a single child, easier to remember.

It happens in the professional sphere, too.

A librarian arranges books in alphabetical chunks. Infants use chunking to remember their dolls! Project management, time blocking, and the Pomodoro technique are all ways of chunking.

Across various facets of everyday life, chunking is immensely popular, which begs the question of why.

Human working memory is limited.

It can only store a few pieces of information, about seven pieces, and recall them accurately later.

However, human ambition is immense. Chunking bridges this gap.

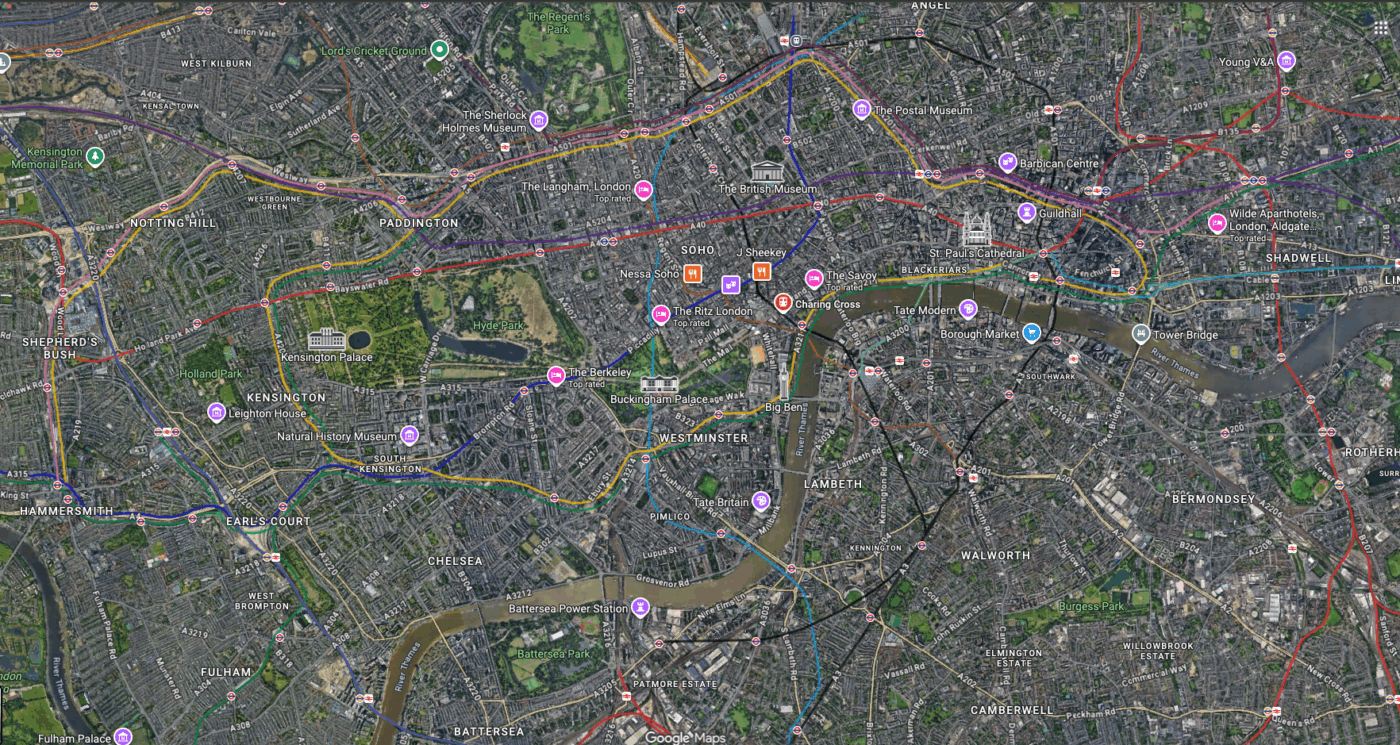

Transport for London, for instance, has the ambition of ensuring all its “taxi drivers know the quickest routes through London’s complicated road network.”

The test for this, known as The Knowledge, evaluates drivers on their memory of a six-mile radius from Charing Cross, which includes 25,000 streets, their directions, one-way streets, dead-ends, restaurants, pubs, shops, and landmarks.

Knowledge boys, a colloquial term for taxi driver candidates, use several memory techniques, one of which is a system they call satelliting, where they chunk locations in a quarter-mile radius around a run’s starting and finishing points, to commit them to memory.

Each of these chunks adds up to larger chunks, forming a hierarchy of memory of the London landscape.

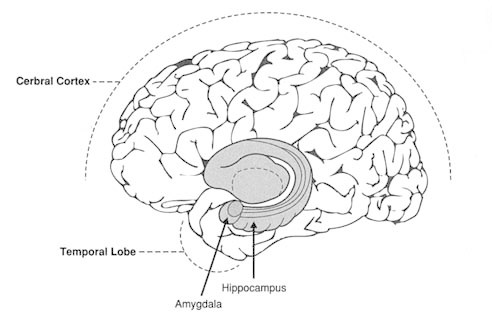

When Eleanor Maguire, a neuroscientist at University College London, studied London cabbies, she found that their posterior hippocampus, part of the brain important for memory, is bigger than average. She also proved that parts of the brain that control memory are malleable and can change even in adulthood. 👀

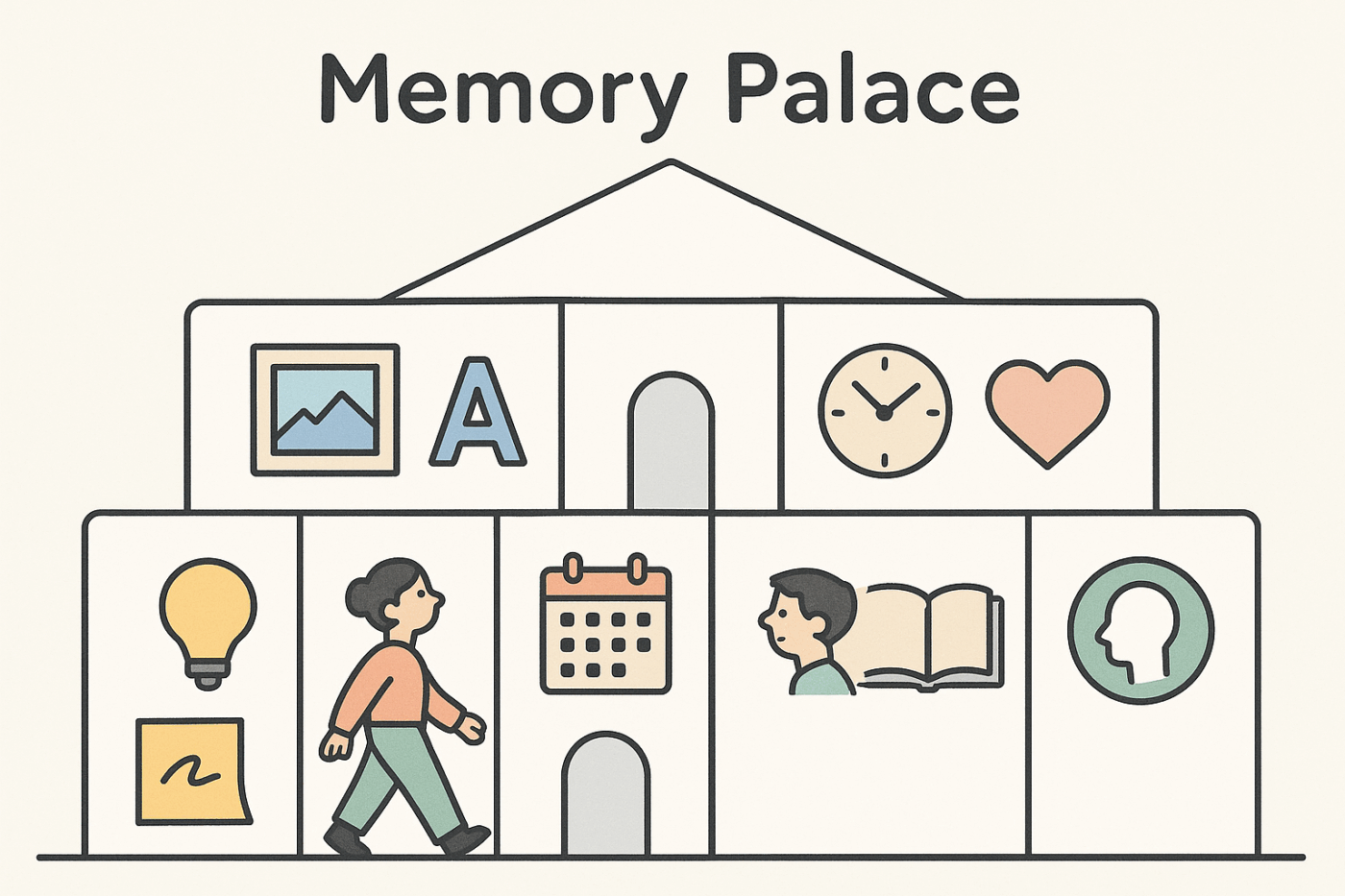

In essence, chunking, and the method of Loci, also known as a memory palace, helps individuals overcome memory limitations, indeed. With continuous practice over the long term, it also reshapes the physical brain to expand human capability closer to its ambition.

Though chunking is incredibly powerful, you don’t need to be climbing the mental Mt. Everest to use it.

I use it to chunk the 14-step Korean skin care routine into manageable phases. At work, many of us schedule deep work in the morning and chunk meetings into the afternoons for simpler time management.

In fact, I’ve chunked this article into sections, sub-sections, paragraphs, and sentences. Something writers do all the time!

While there have been studies around memory, recall, and groups of information earlier, George A. Miller’s 1956 paper titled ‘The Magical Number Seven ± Two: Some Limits On Our Capacity For Processing Information’ marks a seminal point in the study of chunking.

In addition to presenting the idea of chunking as a way to overcome the working memory bottleneck, he also posits that seven (± 2) is the number of chunks one can memorize comfortably. He writes:

What about the seven wonders of the world, the seven seas, the seven deadly sins, the seven daughters of Atlas in the Pleiades, the seven ages of man, the seven levels of hell, the seven primary colors, the seven notes of the musical scale, and the seven days of the week?

Since then, chunking has been studied and has evolved a great deal across spheres.

Psychiatrists use chunking to help verbal working memory in patients with early Alzheimer’s disease. Teachers and educators find chunking useful for school and college students, especially for language learning. Medical students use chunking, and other mnemonics, to remember names of hundreds of drugs.

Expert pilots, like London cabbies, use it for spatial memory to keep track of the various moving parts of an aircraft. Musicians, singers, guitarists, drummers, and so on, use chunking as a way to learn notes, songs, or even read sheet music.

In Music Practice: The Musician’s Guide To Practicing And Mastering Your Instrument Like A Professional, David Dumais writes:

Chunk your music to simplify it. Break it down by phrases and sub-phrases. Do whatever you need to do to keep it simple!

🤔 Check This Out: If cavemen had a to-do list all the way back then, what would be in it?

Across all kinds of memory tasks, chunking works because of its simplicity.

Think of it as carrying one backpack instead of a laptop, a charger, a phone, two shirts, two trousers, two pairs of socks, shoes, toiletries, you get the drift.

This simplicity cleverly hides within it the complex workings of the human brain.

Explaining the concept of memory, Mallika Marshall, MD, Contributing Editor of Harvard Health Publishing, lists the various parts of the brain that come together for storage and recall.

She writes that memory is cataloged in the hippocampus. When the memory is emotionally powerful, the amygdala flags it. Some components are distributed to the cerebral cortex. To recall, we activate the frontal lobes, which then bring information from various parts of the brain.

For example, to remember a scene from your favorite movie might involve pulling in data from the brain’s visual region to recall the backdrop and the actors’ faces, but also information from the language region to remember the dialogue, and perhaps even the auditory region to remember the soundtrack or sound effects. Together, these components form a unique neuronal pattern that lies dormant until you set about remembering it, at which point it is reactivated.

Chunking abstracts this complexity, reducing the burden of processing, memorizing, and storing it in the brain, otherwise known as cognitive load. As a result, the brain is freed up to do more and strengthen expertise.

Even in high-speed sports, which are traditionally seen as a physical task, research shows that chunking can be extremely useful for racers to manage the disparate sensory information they receive in high-stress environments.

We all have days where we think, “What am I even doing here with this task?”

Chunking helps here by organizing information in a way that’s meaningful to the person doing it.

Imagine you’re asked to memorize a dozen animals: cat, chimpanzee, koala bear, kangaroo, tiger, Bengal cat, wolf, mouse, rabbit, fox, penguin, and dalmatian.

A simple chunking would mean organizing them as:

In this case, the chunking builds on ideas we’re already familiar with (pets, forests, Australia) to help place things in context by building associations. In this way, it helps you tap into existing synaptic connections and expand neuroplasticity.

By extension, what if memory isn’t the ultimate goal? Chunking can help with that, too.

You could be task-chunking (or habit stacking, if you’re chunking habits), grouping similar tasks together, so your brain can stay in context and focus on relevant information.

Time-chunking involves breaking down your workday (typically 8 hours) into smaller parts with designated tasks, allowing you to have a more productive day. Agile planning involves breaking down long-term product roadmaps into manageable and deliverable chunks for each sprint, a process also known as ruthless prioritization.

Across all these examples, chunking works because it makes the mess manageable.

It helps individuals absorb more information without giving themselves a headache. As David Epstein writes in his book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World:

Chunking helps explain instances of apparently miraculous, domain-specific memory, from musicians playing long pieces by heart to quarterbacks recognizing patterns of players in a split second and making a decision to throw.

Chunking is a practical skill at its core. The better we group our chunks, the more we remember.

For instance, I can remember the lyrics from a fair bit of songs I listened to as a teenager because the song’s melody helps to segment a text into meaningful chunks.

And that’s just one example. Here are other everyday situations where chunking can really help:

Let’s say you’re taking a first aid course. Instead of trying to memorize 15 separate steps, chunk them into three categories: assess the scene, assist the person, and alert professionals. Within each category, you remember 3–5 actions. Research by Sweller (1988) on cognitive load theory shows that this approach reduces overwhelm and improves retention. Because you’re now operating with better context and understanding.

Forget keeping track of all nine turns to get to a new location. Break your journey into chunks. “Drive to Main Street” (chunk 1), “Take the second left and continue to the gas station” (chunk 2), “Turn right and park by the red building” (chunk 3).

If you’re trying to cook something new, don’t treat each instruction as a separate task.

Group steps into prep, cooking, and finishing. For example, “chop, season, and marinate” is your prep chunk. “Sear, simmer, and stir” is the cooking chunk. Chunking mirrors how chefs operate and helps prevent forgotten steps.

Rather than trying to remember 25 individual items, break your packing list into chunks: clothes, toiletries, electronics, travel documents, and snacks. This reduces the feeling of chaos and makes it easier to check that you have everything.

Kids often get overwhelmed with instructions. If you say, “Brush your teeth, pack your bag, get your shoes, and turn off the lights,” they might forget half of it.

Instead, chunk tasks: “Get ready in the bathroom” (teeth, face, hair), then “pack for school” (bag, lunch, water), then “get out the door” (shoes, lights, jacket). It’s easier for them to succeed, and easier for you to stay calm.

Military personnel often organize their gear in ways that go far beyond simple neatness. The method includes categorization, labeling, and compartmentalization. These three key strategies that serve a specific purpose: enabling fast, accurate retrieval of essential equipment under pressure.

Let’s break that down:

✅ Categorization: Items are grouped by function or mission type. Think medical supplies, communication tools, survival gear, or weapon maintenance kits. Instead of packing gear randomly, soldiers are trained to store and retrieve items by logical groupings. This means that in a high-stress situation, they don’t have to remember every individual item, they just need to know which “category” to reach for.

→ Why it works: This mirrors chunking in memory. According to cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988), grouping related information reduces mental strain, making recall faster and more reliable.

✅ Labeling: Each pouch, container, or compartment is clearly labeled, sometimes by color, symbol, or text. Labels serve as visual cues that trigger recognition, not just recall, which is faster and less mentally demanding

→ Why it works: Chunking often relies on cues and associations. Labels act as “anchors” that help your brain locate the right chunk without having to search through all the information at once.

✅ Compartmentalization: Gear is stored in separate, dedicated compartments, often in modular packs or tactical vests. This prevents items from getting mixed up and allows soldiers to access only what they need in that moment, without sorting through irrelevant tools

→ Why it works: In cognitive psychology, this reflects spatial chunking or keeping related items in physical proximity, which strengthens mental associations and speeds up decision-making.

Chunking works because it makes our brains feel less overloaded. The more you use it, the more automatic it becomes.

Whether you’re learning something new, managing your day, or helping someone else stay organized, chunking turns scattered information into something your brain can handle with ease.

Good chunking is about breaking down anything that seems complex, or has more than “7 ± 2” items, into logical parts. When done right, it can be an extraordinary tool in your armor.

Before you implement chunking, set a goal.

Choose what you want to simplify. This can be anything from KonMari-ing your cluttered desk or building the next AI unicorn.

At this point, don’t worry about the sequence or the size of each step.

Make a comprehensive list of everything you need to do. You can just write it down on a piece of paper or use a to-do list app. Some of these brainstorming templates might help, too.

For example, if you were to declutter your desk, the list would look like:

💡 Pro Tip: Make that list. Don’t judge. If you’re working as a team, chunking with ClickUp Tasks, the six thinking hats technique is a great way to cover all your bases.

Based on all the items you’ve listed, create a handful of chunks that you can manage.

The above list can be categorized into dusting, stationery organizing, document management, etc. Don’t worry if you don’t get everything in yet. You can add chunks in the next step, too.

Under each chunk, add the information or task you’ve identified. The above set of chunks might look like this.

| Dusting and cleaning | Stationery organization | Document management | Digital tasks | Tabletop aesthetics |

| Wipe down the tabletop | Throw away pens that don’t write | Archive letters and documents | Empty recycle bin | Keep just the daily planner on the desk |

| Deep clean keyboard and mouse | Put the markers near the whiteboard | Shred unwanted documents | Digitize the sticky notes | Water the money plant |

Vacuum the chair and organize the wires | Throw away used stationery | Clear the coffee cups |

The whole point of chunking is to make complex tasks simpler. So, tackle the task, do one chunk at a time.

This works as a memorization technique as well.

Let’s say you’re looking to memorize the periodic table. You’d chunk them into metals, non-metals, transition metals, lanthanides, actinides, metalloids, and noble gases.

Start with one, say metals, and memorize them all. Once you’re comfortable, move to the next one.

While chunking is a great technique for memory and organization, it is also prone to the forgetting curve.

So, revise and repeat the process to ensure long-term recall. When you chunk tasks you want to do, but generally don’t, like exercising or meditating, chunking can help form habit loops, too.

If you’ve never actively done chunking, it might seem like a huge process. It doesn’t have to be.

👉🏽 Start small: Begin by trying to memorize a credit card number while standing in a checkout queue or vehicle registration numbers while stuck in traffic. Taking on huge tasks at the start will mean you’ll lose track of time, yet memorize little

👉🏽 Try the memory palace: Popularized by Sherlock Holmes, the memory palace is a way to visualize information as though they are rooms in your brain that you can walk through. Use this technique to organize information spatially

👉🏽 Create mnemonics: For all chunks of a goal or for the bits within each chunk, create mnemonic systems, like an acronym, a story or even a rhyme

👉🏽 Set recall cues: Ever completed the dialogues in your favourite movie the moment a character starts speaking? The beginning of that dialogue is a recall cue, something that triggers the memory of the rest. Set up your own recall cues for what you want to remember

🌷Did You Know: Chunking was believed to be a memory technique that retains information as it is. Musicians were seen as “human tape-recorders” who could play back exactly what they hear. However, this was not the case when they were given atonal music to play back. This showed that chunking isn’t about any group of items. Patterns and familiar structures were critical to recall, writes David Epstein.

While absolutely simple and extremely effective, chunking isn’t the only learning technique there is.

Let’s see how it compares with other common ones.

Spaced repetition is the process of reviewing learned material over different periods of time.

For instance, if you’ve learned a new concept in the morning, spaced repetition recommends reviewing it once in a few hours, a day, a week, two weeks, and so on.

| Chunking | Spaced repetition |

| Encoding technique | Retrieval technique |

| Aids in memorization | Aids in recall |

| Designed to overcome the limits of short-term memory capacity | Designed to overcome the effects of the forgetting curve |

A mindmap is exactly what the term says: A visual map of the thoughts you’re having.

In essence, you’d used a mind map to organize information in a hierarchical and non-linear way.

So, both chunking and mind mapping are encoding techniques.

Good mind maps use chunks too, organizing information across nodes and sub-nodes. Combining chunking with mind mapping helps expand the understanding of complex ideas.

| Chunking | Mind mapping |

| Organizes information as independent units | Organizes information as connected units |

| Focused on grouping similar bits of information | Focused on representing associations and connections between information |

| Not always hierarchical | Always hierarchical |

Note summarization is the process of curating key points from a lecture, presentation, or concept and noting them down for later recall. When you summarize notes in your own words, you’re more likely to remember and recall them.

| Chunking | Note summarization |

| Used to memorize all the information | Used to comprehend concepts and remember salient points |

| Helps remember as it is | Encourages note-taking in your own words |

| Focused on accuracy of recall | Focused on comprehension of ideas |

In a way, chunking is a summary too. It is a list of first-level information. However, not all summarization is chunking.

With all this understanding of the chunking method, if it feels like too much to practice, don’t sweat. We’ll break it down in the next section.

💡 Pro Tip: Chunking, spaced repetition, mind mapping, and note summarization are all complementary techniques that can boost learning when used together.

The most important step in the success of using the chunking method is to set the right goal.

There are various ways you can set and manage your targets. For instance, the SMART goals method is the most effective and popular.

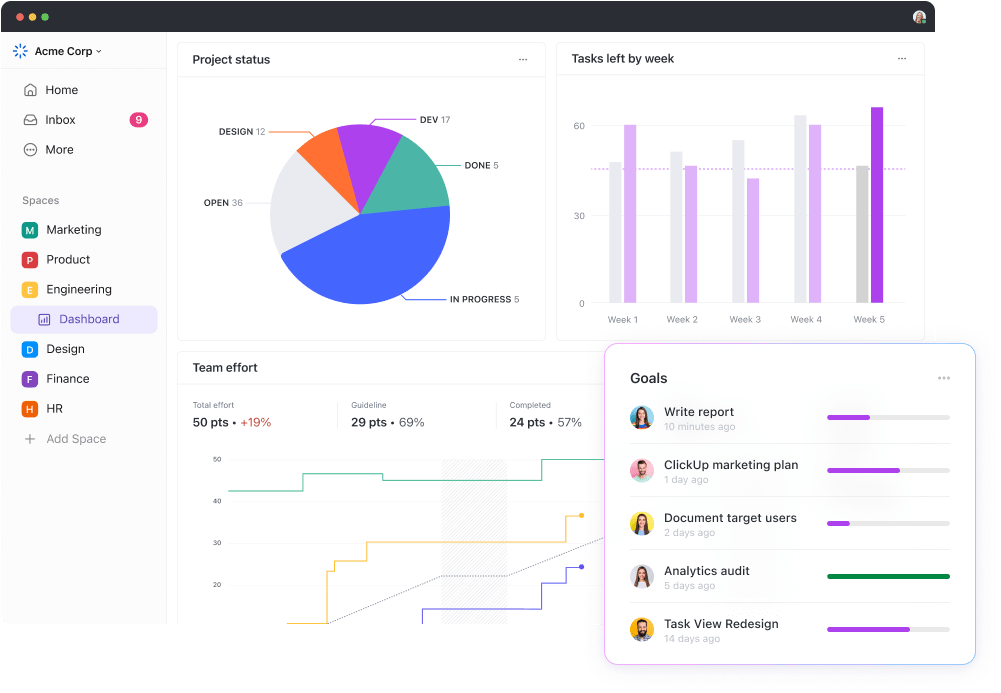

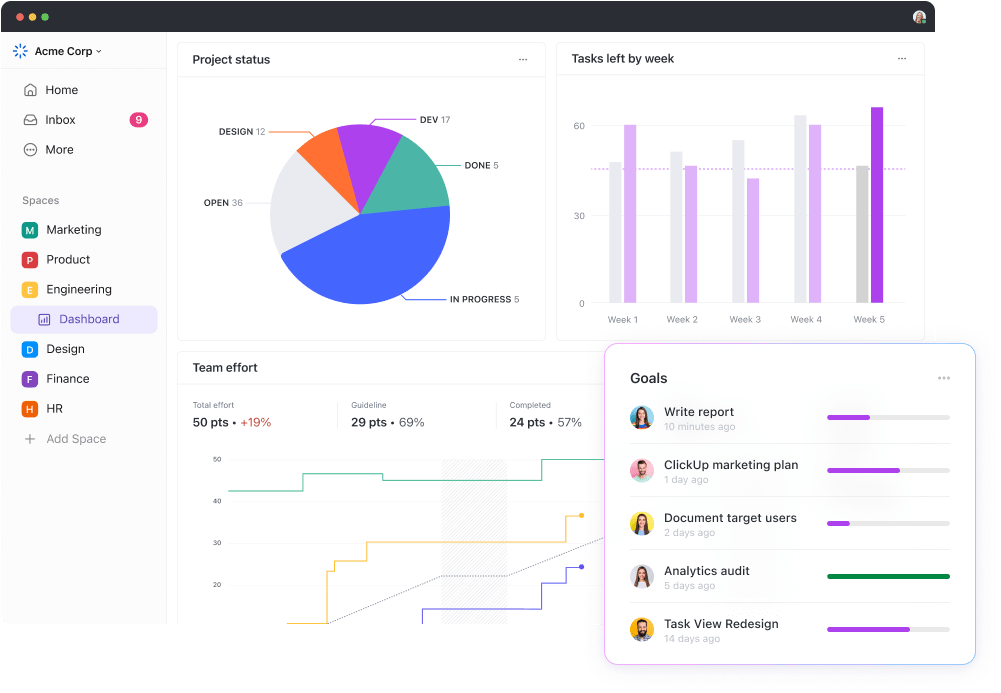

ClickUp Goals is a great way to visualize and make progress on your goals.

Set task targets (complete the UI design for home page by the end of the week), numerical targets (make 12 sales calls every day), currency targets (make $250,000 in new client revenue), or even yes/no targets (do we have an NPS score above 4?)

Once you have a goal, make a list of everything you need to do to accomplish it.

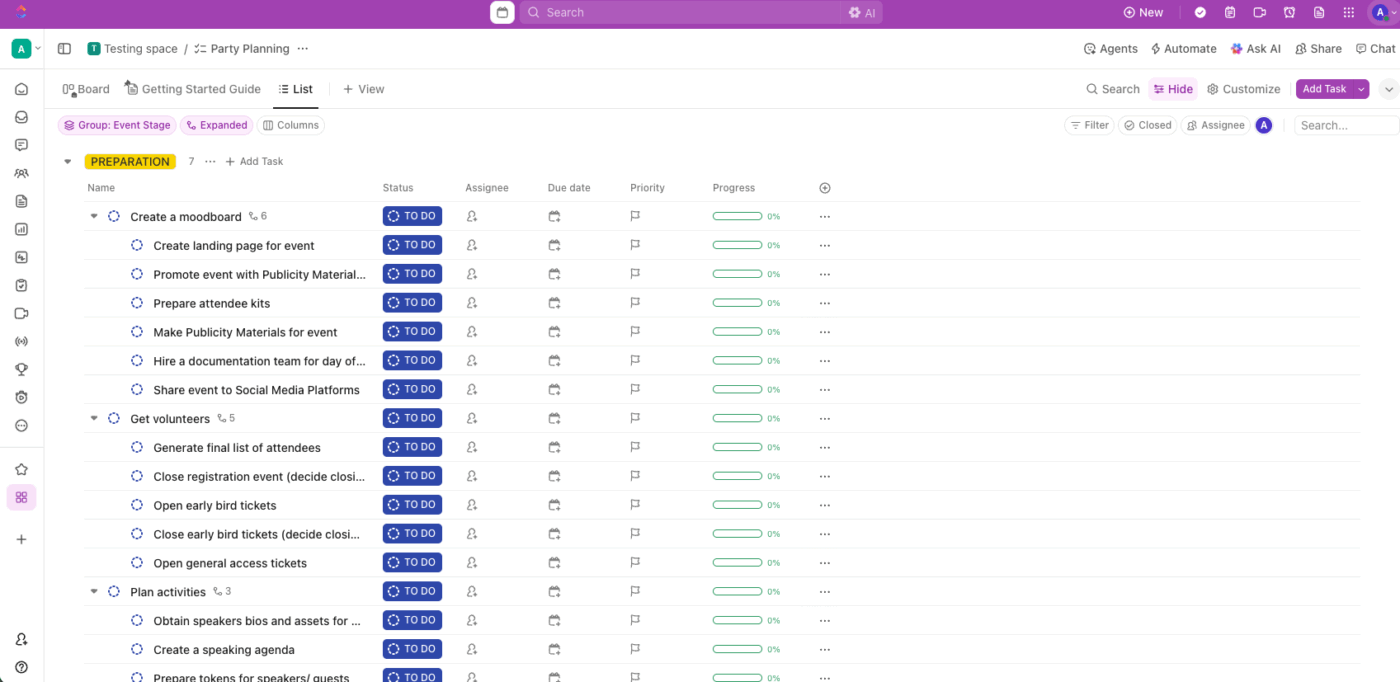

If it’s large enough, break them down into projects. Else, ClickUp Lists and Project Hierachy allow you to add as many tasks as you need.

You can use ClickUp Lists to chunk information in any way you like.

For example, create ClickUp Milestones with chunks of tasks. Add custom statuses to group them by how far you’ve come. And use custom tags like the source of a lead to chunk them that way. You can also create ratings and bring all your five-star accounts together!

🌷Did You Know: A professional chess player would stop seeing the board as 64 individual squares. Instead, they learn to recognize common tactical chunks or formations, such as the “Fianchetto Castle” or the “Isolated Queen Pawn structure.” Recognizing these few complex, pre-stored formations will allow them to grasp the strategic state of the board instantly.

The list view is just the start. ClickUp Views offer a wide range of customizable options.

If you’d like something more visual, the ClickUp Kanban Board helps you see a vertical breakdown of your chunks and the items in each of them.

The ClickUp Prioritization Matrix template and ClickUp Priority Matrix template are other ways you can look at the work at hand. By chunking work based on priority, you can declutter the task list and focus on what matters.

Once you’ve learned a concept, there are several ways in which you can practice spaced repetition and revision for better recall.

✅ Review with AI: Set up your own personal sparring partner with ClickUp Brain. Prompt it with the information you are trying to learn and ask it to:

✅ Answer quizzes: Nothing aids learning more than being asked to explain it. Set up quizzes for yourself to review your learning actively. Tools like Quizlet are great for this.

✅ Use flash cards: Since time immemorial, flash cards have helped with memory and recall. Do it digitally and carry it with you anywhere using tools like the free and open source Anki.

Here are some more productivity hacks to help you:

230 hours of practice increases memory span from 7 to 79 digits, finds a study.

With an appropriate mnemonic system, there is seemingly no limit to memory performance with practice.

Chunking is one such system. It helps humans memorize and organize anything, however complex, and recall with integrity later.

But there’s more.

It also offers a way to manage the information overload coming your way. That includes putting disparate information in neat little boxes with a label so you can access them as you need.

By corollary, you can also put away things you don’t need at the moment, dramatically reducing stress. Depending on the tasks you’re doing, you’ll review your chunks over and over. Less stressful, less cognitive load, less overwhelm.

When you combine chunking with spaced repetition and active review, you can see for yourself how much you know. Naturally, this builds confidence.

Beyond individual uses, chunking also helps build standards for things in society. For instance, in the US, it is standard practice to chunk telephone numbers as 3-3-4 digits. Website menus are typically chunked into services, solutions, industries, resources, etc.

In that sense, it wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that thoughtful chunking creates a world that’s easier to memorize and to live in.

Chunking is one of those techniques that feels foolproof, until it’s not.

Many people jump in thinking they’re simplifying their work, only to end up with a mess of confusing mini-tasks or oversized “chunks” that still feel impossible to start.

The trick is not just to divide your workload, but to divide it wisely. Here are the classic chunking mistakes to watch out for.

Miller posits that 7 ± 2 is the number of chunks human memory can hold. Multiple researchers since then have shown this is more or less right. To err on the side of caution, create no more than seven chunks for each concept. If you’re a beginner, you might want to start with much fewer chunks.

What if you remember the chunk but not the items in it? That would be useless. So, pay attention to the number of items you put into each chunk. Studies show that the optimal number of items in each chunk is 3-4.

Chunking is useful only if it makes sense to you. For instance, if you chunk your grocery items under the labels A, B, C, and D, and add items at random into them, you’re unlikely to recall any of it.

For best memorization and recall:

Sometimes, you memorize things just for the sake of it, like the names of all the rivers in the US. Often, you do so to achieve a goal. While creating chunks, make sure you’re working in service of that goal.

For example, grocery list chunking is to help with shopping, so choosing each supermarket aisle as a chunk is a good idea. In the school curriculum, related chapters are chunked together so children can build synaptic connections while they memorize their lessons.

Everyone goes through the forgetting curve. Whether you use the chunking method or not, you will forget information over time. The only way to avoid this is through systematic reviews.

Schedule reviews at intervals of a few hours, one day, a few days, a few weeks, etc. If it is information you’re not likely to access for extended periods of time, revise each quarter/year.

💡 Pro Tip: If it feels tedious, try the bullet journaling practice to make it more fun and less intimidating.

While chunking has long been studied as a way to help humans improve memory, it can transform machines, too. Here’s how.

Chunking is a critical and highly common process in the human brain.

Artificial intelligence, which, in essence, tries to mimic human thinking processes, has a great deal to learn from chunking.

✅ Limiting token size: Training an AI model with Natural Language Processing (NLP) involves providing input sources. Often, there is a limit to the token size of these inputs. For example, the maximum input text length of the Azure OpenAI text-embedding-ada-002 model is 8000 tokens. Chunking helps break down documents into pieces for Large Language Models (LLM) to process effectively

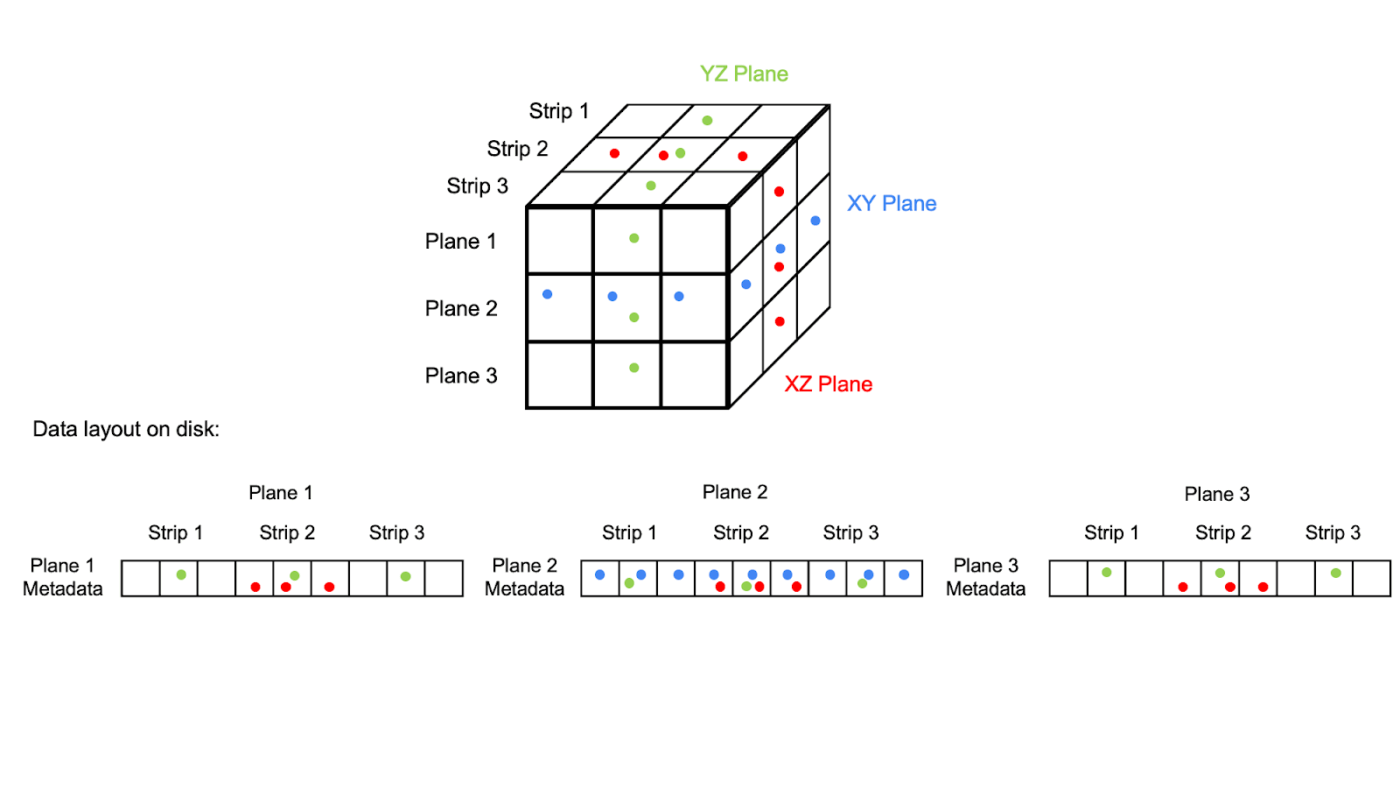

✅ Chunking in time series data: Chunking a text is easy. Cut where a sentence or paragraph ends and you have a logical chunk. What if you have a continuous stream of numerical data, such as stock prices or weather readings? Typically, this is done chronologically, i.e., creating chunks for “the last 30 days” or “daily readings.”

✅ Chunking in image data: Large images are chunked by breaking them into smaller, uniform rectangular pieces called patches or tiles, a popular technique in modern computer vision models, such as Vision Transformers (ViT)

✅ Goal-based chunking: Imagine you’re in a meeting and you need notes. The chunks you create are useless if they’re organized by the person who spoke or the time they spoke. You need contextual chunking here, into salient points, feedback, decisions, action items, etc. That’s exactly what ClickUp Brain’s AI Notetaker does

✅ Chunk sizing: Unlike the human brain, computers can have a larger working memory. This means that AI models can have any number of chunks in fixed or variable size. There are pros and cons to both

| Aspects | Fixed chunks | Variable chunks |

| Definition | Divides data into chunks of uniform length | Divides data into logical or meaningful chunks |

| Techniques | Length of data irrespective of context | Recursive splitting, semantic chunking, etc. based on context |

| Best for | Simplicity & Speed | Accuracy & Coherence |

| Pros | High computational efficiency and predictable performance | High semantic integrity and contextual richness |

| Cons | Possible context fragmentation and loss of coherence | Increased complexity and higher computational cost |

✅ Overlapping: Chunking is a compression technique, not a relational one, which means there is a possibility of context loss. In machine learning, this can create statistically accurate output that’s disconnected from context. Scientists overcome this challenge with a concept called overlapping. By sharing a portion of the data from the previous chunk to the current chunk, overlapping enables LLMs to identify and connect with the continuation in the context

Chunking often gets treated like the superhero of memory techniques, swooping in to save the day when information overload strikes.

But as much as we’d love for chunking to be the memory equivalent of duct tape (fixing everything, forever), it definitely can’t carry the weight of all our cognitive shortcomings on its compact, neatly grouped shoulders.

So, before we hand chunking the keys to our mental kingdom, let’s take a closer look at where it stumbles, fumbles, and occasionally trips over:

❗️Difficulty with novel visual data: Chunking is great for sequential, verbal, or highly structured information (like digits). It is less effective for processing large amounts of complex visual or spatial information, such as a map of unfamiliar territories or a complex schematic diagram

❗️The debate over 7±2: Cognitive psychologist Nelson Cowan posits that the average capacity of the central memory store is only about four chunks. In today’s world of omnipresent distraction, it might even be lower

❗️Domain specificity: Even with chunking, it’s not easy for a Grandmaster to memorize hundreds of songs. Or for someone to memorize all the rivers in a country they’re not familiar with. The success of chunking relies heavily on the expertise of the learner in their domain

❗️No shortcuts: Chunking is a simpler way to crunch large amounts of information, yes. But it’s by no means a shortcut. Mastery can only be built through extensive, dedicated practice, which takes time

In the world of digitization, AI, and automation, memory is not as valuable a skill as it used to be.

Not many remember beyond their own phone number and their spouse’s. All information is just a click away, right in our pockets. That doesn’t mean chunking is outdated.

I’ve noticed that working on my memory with the chunking method improves my focus.

For instance, I plan all of my writing around five chunks: What, when/where, why, who, and how. This helps stay in the process and focus on the idea at hand. More importantly, these chunks make it easier for me to return to work after a distraction.

Researchers trying to recreate human intelligence into machines find the research on chunking extremely valuable. In Large Language Models (LLMs), chunking helps process vast amounts of data more efficiently. It ensures that models maintain context and retrieve accurate information without exceeding token limits, also known as Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). Computational neuroscientists are exploring chunking in the context of a speed-accuracy trade-off, essentially paving the way for more effective chunking based on your goals.

In cognitive neuroscience and modeling, ‘egocentric chunking’ offers a better understanding of the workings of a predictive brain. In neuroscience, ‘action chunking’ investigates how the brain organizes complex motor skills (like tying a shoe or playing a musical phrase) into neural sequences, offering pathways for enhanced motor learning and rehabilitation.

Researchers are also studying ‘synaptic augmentation,’ which is the brain’s ability to temporarily suppress groups of items without permanently erasing them from working memory.

Possibilities are truly endless.

This old aphorism (often attributed to Desmond Tutu) argues that even the most intimidating and large tasks can be completed if you take them one step at a time.

The chunking method offers an upgrade on that.

In times when we’re biohacking and chasing superhuman productivity, chunking offers a real human way of experiencing the world through memory. It helps us understand the human psyche better, showing us what differentiates Grandmasters and high-performing sportspeople from the rest.

Or, as I’d like to see it, chunking tells us that we are capable of the same things Grandmasters and high-performing sportspeople are.

Happy chunking ahead, folks!

Chunking is a memory retention technique in which you break down a large piece of information into smaller, manageable chunks.

Chunking is an encoding strategy used to organize new information and prepare it for long-term storage. Spaced repetition is a retrieval strategy used to reinforce and strengthen those newly formed chunks over time. They are complementary techniques.

Chunking is everywhere. Some of the real-world examples of chunking are:

– Memorizing a phone number in chunks of 3-3-4

– Organizing projects into chunks of tasks across stages

– Learning a language with chunks of related words

– Training to fly a plane by chunking instructions together

– Remembering 100+ medicines through chunks of similar/complementary drugs

You don’t need anything—even pen-and-paper—to perform chunking successfully. However, there are many tools that can help. These include note-taking methods such as the Cornell system, digital flashcard applications like Anki, and generative AI tools like ClickUp.

Yes, modern AI tools like ClickUp help in various ways, such as creating hierarchical structures by breaking down large goals into nested Folders, Lists, and Tasks, or summarizing long texts into shorter, more memorable chunks. They can also help with identifying salient points (which you can use as chunks).

Choosing the correct method depends on the type of information you want to memorize. Just ensure that they are inherently meaningful to you and the task at hand.

– If you’re making a list, choose logical categories (like a supermarket aisle for a grocery list)

– While studying history or memorizing a schedule, choose chronology (like researching World Wars or planning to attend the World Cup)

– When planning a project, choose logical chunks or phases (like defining a goal, planning channels, creating ads, launching campaigns, reporting performance, etc., for a marketing campaign)

-In writing, a content writing template might chunk the article into sections, sub-sections, paragraphs, and sentences

Chunking helps absorb and retain information effectively. It reduces cognitive load and the stress of having to remember things. However, it isn’t effective unless done right. If you create too many chunks or group items arbitrarily, you might feel like the burden is higher than before.

© 2026 ClickUp