The Productivity Killers

Even with the best techniques and tools, certain patterns and behaviors systematically undermine productivity. Understanding these productivity killers is the first step toward addressing them effectively.

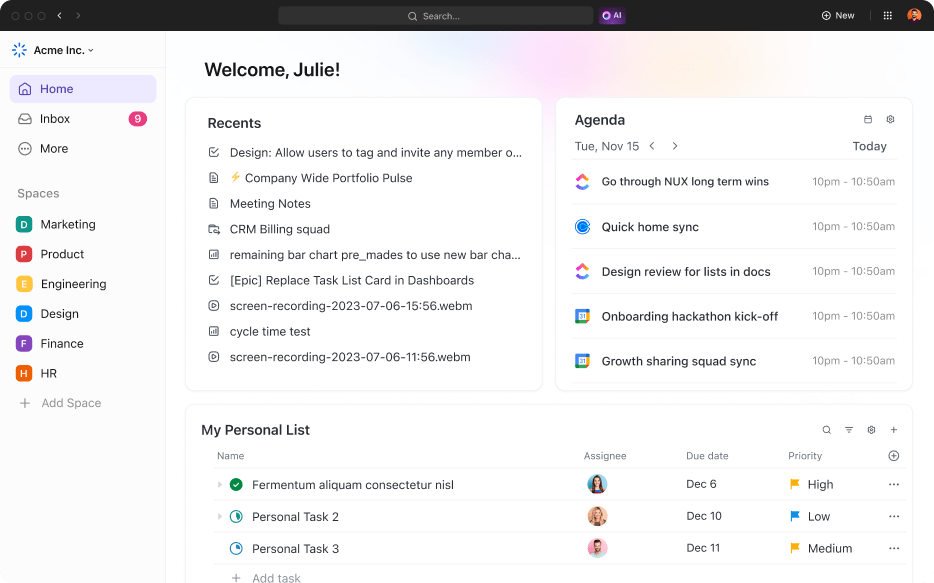

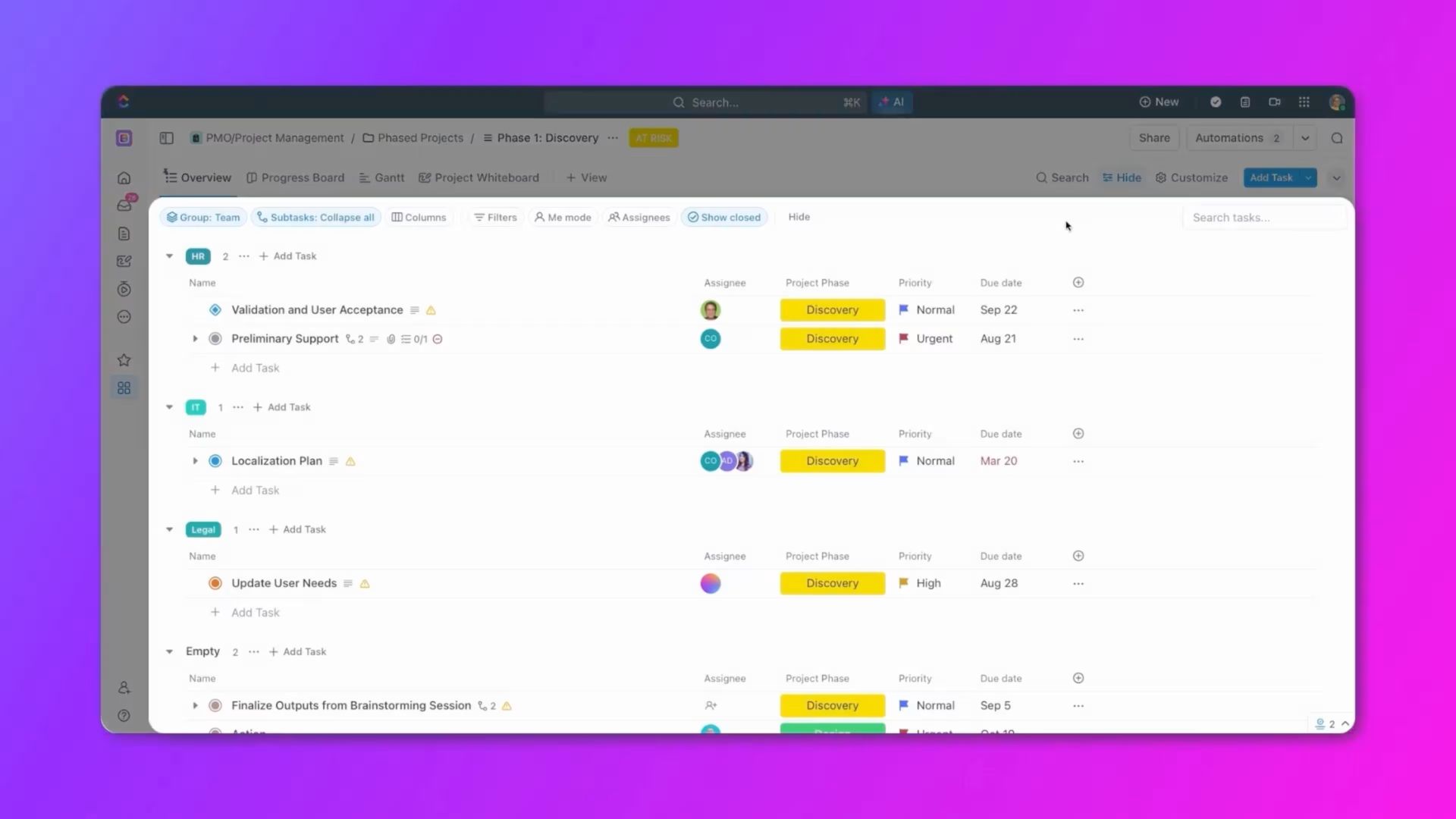

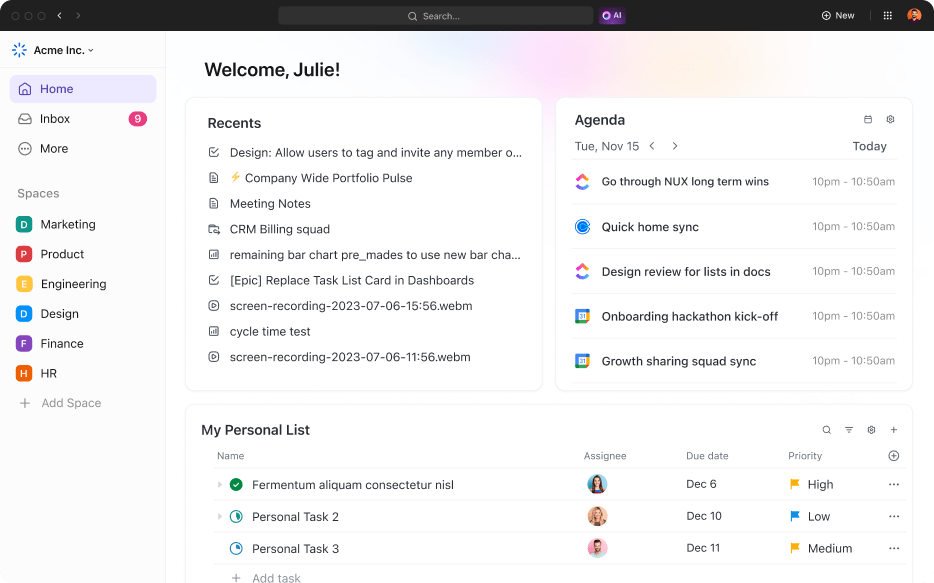

Context switching—bouncing between apps and tasks—fragments your attention and drains mental energy. Each switch requires your brain to reorient, reload context, and refocus on the new task.

Research shows that it can take 23 minutes to fully recover focus after an interruption. When you switch tasks every few minutes, you never reach deep focus at all.

Information overload compounds this problem by bombarding you with more data than you can meaningfully process. Every notification, email, and message adds to the cognitive load you're carrying.

Your brain wasn't designed to track dozens of simultaneous conversations and hundreds of pending tasks. The result is a constant sense of overwhelm that makes it difficult to focus on anything deeply.

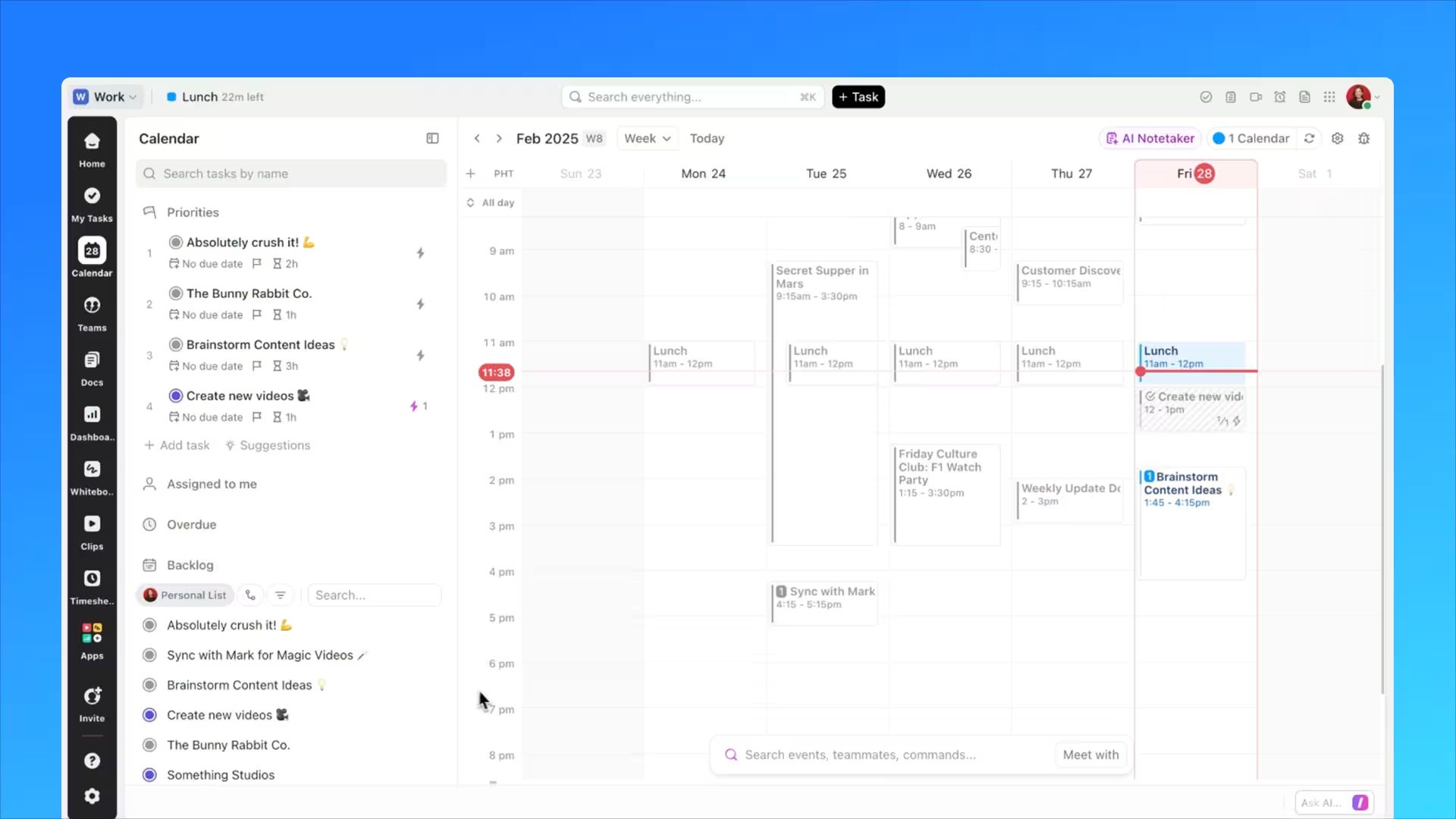

Time blindness—difficulty accurately estimating or perceiving time passage—creates its own challenges, particularly for people with ADHD.

What feels like 15 minutes might be an hour, or vice versa. This makes planning difficult and deadlines feel like they arrive without warning.

The solution involves external structure: visible timers, calendar blocking with buffer periods, and regular check-ins throughout the day.

Perhaps the most insidious productivity killer is toxic productivity—when healthy ambition crosses into compulsive overwork driven by anxiety rather than purpose.

This manifests as inability to rest without guilt, measuring self-worth through output alone, and sacrificing health and relationships for marginal productivity gains. You might hit impressive metrics while slowly burning out and damaging what matters most.

Recognizing toxic productivity patterns is the first step toward more sustainable approaches that value wellbeing alongside achievement.

Mental and Emotional Barriers

Beyond external productivity killers, internal barriers often prove even more challenging to address. Mental blocks—psychological barriers that prevent starting or progressing on tasks—rarely stem from laziness despite what we tell ourselves.

More often, they arise from perfectionism (afraid the work won't meet your standards), fear of failure (worried about the outcome), or unclear direction (unsure how to begin or proceed).

Ironically, productivity procrastination represents a particularly tricky form of avoidance. You spend time researching productivity systems, organizing tools, and planning workflows. All of this feels productive, but serves as a way to avoid doing actual work.

You're busy, you're learning, you're optimizing... but you're not making progress on what actually matters. This form of procrastination is especially insidious because it disguises itself as self-improvement.

Managing time blindness requires accepting that internal time perception isn't reliable and building external scaffolding instead.

- Set multiple reminders for important deadlines.

- Use visible countdown timers that show time passing.

- Create time blocks with generous buffer periods between commitments.

The goal is creating systems that work with your brain rather than fighting against how it naturally operates.

Decision Fatigue and Overwhelm

Every decision you make depletes a finite pool of mental energy. Learning how to make decisions efficiently preserves this energy for choices that genuinely matter.

Research shows that willpower and decision-making draw from the same limited resource, which is why it's harder to resist temptation after a long day of difficult decisions.

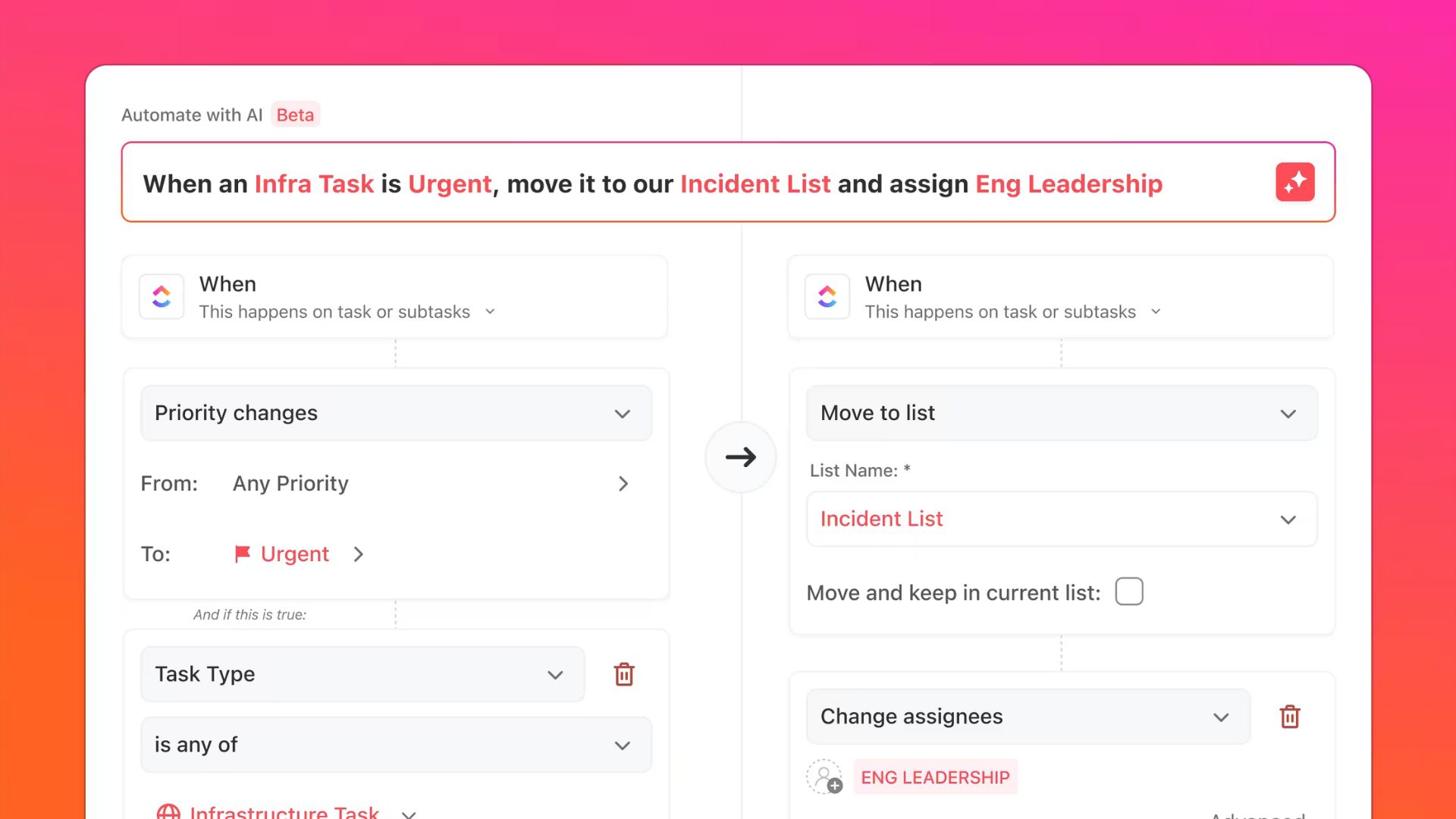

This is why routines matter so much for productivity. When you automate low-stakes decisions like what to eat for breakfast, what to wear, when to exercise, you preserve decision-making capacity for work that truly requires it.

Steve Jobs and Mark Zuckerberg famously wore the same outfit daily not because they lacked fashion sense, but because they refused to waste mental energy on clothing decisions.

It's also equally helpful to distinguish between routines and schedules. Routines are habitual sequences that you perform in the same order: morning ritual, evening wind-down, weekly planning session.

Schedules assign specific times to activities: meeting at 2pm, lunch at noon, gym at 6am. Your morning routine might always include exercise, breakfast, and reviewing daily priorities, but when each occurs and how long it takes can flex based on the day's schedule.

This combination of routine (what you do) and flexible scheduling (when you do it) provides structure without rigidity.

Optimizing for Your Reality

Productivity advice often assumes everyone operates the same way, but individual differences matter enormously. How to have a productive day looks completely different for a night owl versus someone who naturally wakes energized at dawn.

Night owls learning how to be productive at night need strategies that honor their natural energy cycles rather than fighting them.

This might mean protecting evening hours for deep work, scheduling meetings during the afternoon slump rather than morning, and building in morning transition time before demanding tasks. Fighting your your natural sleep-wake preference creates unnecessary friction.

Similarly, the low dopamine morning routine recognizes that some people need gentle, stimulating activities to gradually wake up rather than immediately launching into demanding work.

A slow morning with coffee, light reading, and gentle movement might enable better focus later than trying to force productivity when your brain hasn't fully engaged yet.

The encouraging news is that you're not stuck with your current productivity levels. Understanding how to change your brain through consistent practice and habit formation reveals that improvement is always possible.

Your brain's ability to form new neural pathways means that repeated behaviors literally reshape your brain over time.

Research on micro habits shows that starting incredibly small builds momentum and neural pathways that eventually enable larger changes.

You don't need massive willpower to floss one tooth, do one pushup, or write one sentence. But one becomes two, becomes five, becomes a habit that runs automatically.

The question isn't whether change is possible, it demonstrably is. The question is whether you're willing to start small and stay consistent long enough for neural pathways to form and strengthen.

Productivity challenges are normal, not character flaws. Context switching, mental blocks, decision fatigue, and misalignment with your natural rhythms create friction regardless of how disciplined you are.

The solution isn't trying harder with brute force, but instead, it's understanding the specific obstacles you face and building systems that work with your brain rather than against it.